...no, not because of any problem or emergency...but today's flight was considered complete from beginning to end in only 0.5 hours (including time on the ground). At issue was wind and a time constraint to be back home by dark (for non-flying reasons).

The opportunity, however, was that I would be able to take my other two kids up on one of the last decent days we're supposed to have for the next week or so. A cold front is moving in, and we have snow forecast until the weekend. The by-product was an AIRMET for turbulence due to us being in the "gears" of the tightly spaced high and low. Nevertheless, always the optimist, I kept my eye on the winds, and when they got below 10 knots, around the time that school let out, it was looking good.

There were still very strong winds just a few thousand feet up, so I planned on keeping it low and slow. I did my best not to rush through anything, since I figured that whatever time we could be in the sky was going to be worth the trouble. It was a busy time (and maybe a lot of other folks were taking advantage of the unseasonably mild weather) and we had to spend a few minutes holding at the runway. Once we were cleared, we made a smooth climb out. I had requested 6,500 feet, but as we climbed up into 4,500 it started to get a little bumpy. I amended my request to simply stay at that altitude, and we made a wide circle over town.

I was aiming for the next town over, about ten miles or so to the west. As we got about 8 miles out, I could feel the burbles of the higher speed wind above us, and I was tired of looking into the sun, so we made the turnaround and headed back. The kids (11 and 5) were having a great time, and no one had any problem with airsickness. They were surprised at how loud the plane was at takeoff, but did well considering I had to stay on the radio almost the whole time. I had a chance to explain my job during preflight and that, as helpful as they wanted to be, I had to make sure personally that everything was ship-shape and that there wouldn't be very much conversation once in the air.

The flight was summed up as "awesome" and "totally cool" by the experts. What ended up being a glorified trip around the pattern for me was nonetheless a great first flight for them. And, hey, when all was said and done, it only cost fifty bucks in rental time. What a deal! We'll hope that the weather isn't quite as bad as forecast, and maybe there can be another flight in the near future.

Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Friday, October 31, 2008

Spousal Consent

It didn't take much to convince me to ditch work today due to the continued good weather here. On top of that, my wife was also available to take the opportunity for a first flight. A quick check of the forecast was all it took to confirm that days like this just don't really get better. A nice, quiet Friday, high clouds, cool air, light winds, and a nice airplane. That, and a significant other...made all the more significant due to a willingness to even indulge my flight training in the first place, let alone strap in and join me in the sky.

Today was actually a different craft than yesterday, but virtually identical other than a different radio stack and a couple of extra horsepower under the hood. It made no difference, and I had spent last night going over the performance figures that I copied after yesterday's flight.

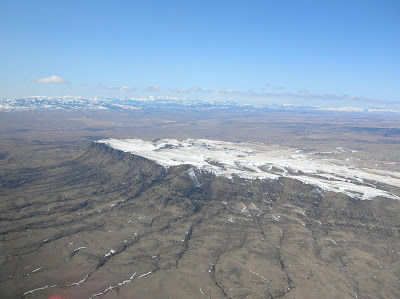

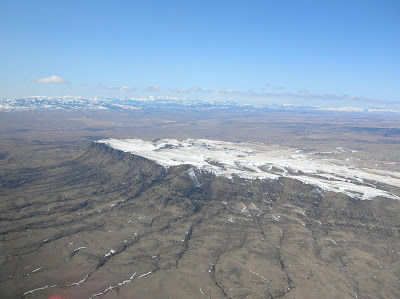

We planned on making a circuit around the nearby hills, but a 25 knot headwind on the first leg tightened up our flight a bit closer to the city. We made a steady climbout, with only a couple of course deviations from ATC for traffic departing behind us. Then we were on our own, keeping it low and slow over the Yellowstone River and surrounding ranch and agricultural land.

My passenger was (probably typically for a first-timer) a bit nervous about the whole undertaking, but we kept things calm and the weather cooperated, too. Shallow banks (all to the left), steady altitude and power settings, and only a few burbles of wind made for a smooth flight all the way around. Smooth enough that this will hopefully be the first of more trips in the future.

We stayed up for an hour, and came in for a passenger-friendly landing. Not only was the flight successful, but it demonstrated that all the money we've invested in my little hobby has hopefully been well spent.

Today was actually a different craft than yesterday, but virtually identical other than a different radio stack and a couple of extra horsepower under the hood. It made no difference, and I had spent last night going over the performance figures that I copied after yesterday's flight.

We planned on making a circuit around the nearby hills, but a 25 knot headwind on the first leg tightened up our flight a bit closer to the city. We made a steady climbout, with only a couple of course deviations from ATC for traffic departing behind us. Then we were on our own, keeping it low and slow over the Yellowstone River and surrounding ranch and agricultural land.

My passenger was (probably typically for a first-timer) a bit nervous about the whole undertaking, but we kept things calm and the weather cooperated, too. Shallow banks (all to the left), steady altitude and power settings, and only a few burbles of wind made for a smooth flight all the way around. Smooth enough that this will hopefully be the first of more trips in the future.

We stayed up for an hour, and came in for a passenger-friendly landing. Not only was the flight successful, but it demonstrated that all the money we've invested in my little hobby has hopefully been well spent.

Thursday, October 30, 2008

...where I left off

It's hard to believe that so much time has passed. My family is in a new city and a new house, and I have been struggling to find some time to get up to a new airport, find an instructor, and get checked out in a new (old) plane. Finally, today was the day. The entire country appears to be dominated by one or more high pressure systems, and for the end of October, it was a beautiful day for a flight. Wouldn't it have been nice if my flying skills were as crisp as the weather...

Keeping in mind that my logbook is only about 84 hours thick, it wouldn't take long for the rust to set in. Compound that with the fact that I have been flying a 2-seat, low wing, fuel-injected DA-20 -- now I'm in the left seat of the venerable Cessna 172...from 1969 no less. Virtually identical to my dad's former craft, it's not unfamiliar territory, but it felt like transitioning from a Mazda Miata to a Chevy Suburban.

Today was a checkout to allow me unrestricted rental privileges, and the instructor (whom I had met many months ago before moving here) thought it wouldn't take long to get me up to speed. Indeed, after some slow flight and stalls, all it took was a few touch-and-go's to get in the groove. But it wasn't a cake walk, either.

Yoke vs. Stick. High wing vs. low. Electric trim vs. not... Remember the carb heat...

Different flap controls, different speeds, different sight pictures during landing

All of the physical sensations are the same, but different. The sounds are different, the controls are firmer, and that first landing was a bugger.

After completely embarassing myself and thinking I was a pretty lousy representative for any flight school that would allow such antics, it came together. A little more finesse with the throttle, a lot more finesse with the pitch, and I was starting to get it. And each landing after the first was nearly picture perfect, if your picture somehow blots out the runway centerline...

At least by the end, I had it pretty well greased onto the blacktop (even with a crosswind, thank you very much) and the instructor was satisfied that I would not be too much of a risk to myself or others. So, not only have I moved up to a "complex" aircraft (four seats and carburetor heat), but I'm happy to know that the time off hasn't cost me too much of my skill. Of course, now I'm on the pay-as-you-play plan, so we'll see just how long the next hiatus will be.

Keeping in mind that my logbook is only about 84 hours thick, it wouldn't take long for the rust to set in. Compound that with the fact that I have been flying a 2-seat, low wing, fuel-injected DA-20 -- now I'm in the left seat of the venerable Cessna 172...from 1969 no less. Virtually identical to my dad's former craft, it's not unfamiliar territory, but it felt like transitioning from a Mazda Miata to a Chevy Suburban.

Today was a checkout to allow me unrestricted rental privileges, and the instructor (whom I had met many months ago before moving here) thought it wouldn't take long to get me up to speed. Indeed, after some slow flight and stalls, all it took was a few touch-and-go's to get in the groove. But it wasn't a cake walk, either.

Yoke vs. Stick. High wing vs. low. Electric trim vs. not... Remember the carb heat...

Different flap controls, different speeds, different sight pictures during landing

All of the physical sensations are the same, but different. The sounds are different, the controls are firmer, and that first landing was a bugger.

After completely embarassing myself and thinking I was a pretty lousy representative for any flight school that would allow such antics, it came together. A little more finesse with the throttle, a lot more finesse with the pitch, and I was starting to get it. And each landing after the first was nearly picture perfect, if your picture somehow blots out the runway centerline...

At least by the end, I had it pretty well greased onto the blacktop (even with a crosswind, thank you very much) and the instructor was satisfied that I would not be too much of a risk to myself or others. So, not only have I moved up to a "complex" aircraft (four seats and carburetor heat), but I'm happy to know that the time off hasn't cost me too much of my skill. Of course, now I'm on the pay-as-you-play plan, so we'll see just how long the next hiatus will be.

Monday, July 21, 2008

Rainy Monday

The trip back from Salt Lake City was intended to take advantage of a nice high pressure area over the western U.S. While it has held up mostly as expected, it appears that a southerly flow (maybe even from hurricane Fausto?) brought more moisture than originally forecast. I had seen that the forecast changed from mostly clear to overcast, and then scattered showers were added to the mix. Even so, the perpetual afternoon thunderstorms were also still expected.

On the drive to the airport, I kept a watchful eye to the north to see which side of the Salt Lake valley looked the best. There was a nearly solid curtain of showers across the valley, but I could still make out Antelope Island on the west side, so I decided on that direction. This was different than what I had mapped out last night, as I tried to tighten up the route a bit to make it in one shot with no fuel stops. Nevertheless, the clouds were high up and visibility below 12,000 feet was at least 10 miles, so everything was legal. The only concern was my comfort level with venturing off into some light precipitation.

On the drive to the airport, I kept a watchful eye to the north to see which side of the Salt Lake valley looked the best. There was a nearly solid curtain of showers across the valley, but I could still make out Antelope Island on the west side, so I decided on that direction. This was different than what I had mapped out last night, as I tried to tighten up the route a bit to make it in one shot with no fuel stops. Nevertheless, the clouds were high up and visibility below 12,000 feet was at least 10 miles, so everything was legal. The only concern was my comfort level with venturing off into some light precipitation.

As before, I tried to obtain flight following while on the ground at U42, via the Clearance Delivery frequency. I was simply told to remain clear of the Class B and contact approach for a VFR transition. As I sat on the ramp with the engine running, I looked over the charts for another few minutes, to mentally assign myself the proper altitudes at the proper sectors, at least until otherwise directed.

It was even smoother today than on the trip down, due to the cloud cover, so I thought that would continue as I moved north to outrun the rain. As it happened, Approach vectored me further out to the west than I really wanted to be, and I had to stay fairly low. This, combined with the now-steady rain, was starting to give me concern. As I reached Antelope Island, I requested to go direct to Ogden (OGD) since the rain looked at least a bit lighter that way (and it was more on my desired route). I was allowed to turn east as long as I stayed low (about 1,700 AGL at this point).

I puttered along, with the rain not really causing me much trouble, but lowering the visibility through the canopy. I finally made it out the north side of the Class B, and was cleared to proceed on course. I planned to fly a standard VFR altitude of 11,500 feet, but the clouds were lower in this area, so I had to stay a bit lower. I was able to "cheat" a little, by staying around 10,000 feet over terrain that had risen to about 7,000 (so, with less than 3,000 AGL, exempt from the "hemispheric rule"). I asked a few times what the precipitation looked like to the north, and was basically told that "what you see is what it is". So I continued to dodge heavier showers and aim for the higher visibility all the way up to Malad City, Idaho.

There, I could look back and see the rain from the other side. It was still overcast, but the clouds were much higher, there was the rare spot of sunlight peeking through, and I could climb up to 11,500 as planned. This was all the more desirable, since 10,000 had put me under the radar coverage, so I had to call ZLC back and request it again.

The rest of the flight went on without incident, although I did still pick up some early-afternoon thermal turbulence in Montana. I was happy to have successfully navigated and changed course as necessary to thread through the rain. It was also nice to have spent so much time in the air traffic environment. If you haven't yet given it a try, go for it!

On the drive to the airport, I kept a watchful eye to the north to see which side of the Salt Lake valley looked the best. There was a nearly solid curtain of showers across the valley, but I could still make out Antelope Island on the west side, so I decided on that direction. This was different than what I had mapped out last night, as I tried to tighten up the route a bit to make it in one shot with no fuel stops. Nevertheless, the clouds were high up and visibility below 12,000 feet was at least 10 miles, so everything was legal. The only concern was my comfort level with venturing off into some light precipitation.

On the drive to the airport, I kept a watchful eye to the north to see which side of the Salt Lake valley looked the best. There was a nearly solid curtain of showers across the valley, but I could still make out Antelope Island on the west side, so I decided on that direction. This was different than what I had mapped out last night, as I tried to tighten up the route a bit to make it in one shot with no fuel stops. Nevertheless, the clouds were high up and visibility below 12,000 feet was at least 10 miles, so everything was legal. The only concern was my comfort level with venturing off into some light precipitation.As before, I tried to obtain flight following while on the ground at U42, via the Clearance Delivery frequency. I was simply told to remain clear of the Class B and contact approach for a VFR transition. As I sat on the ramp with the engine running, I looked over the charts for another few minutes, to mentally assign myself the proper altitudes at the proper sectors, at least until otherwise directed.

It was even smoother today than on the trip down, due to the cloud cover, so I thought that would continue as I moved north to outrun the rain. As it happened, Approach vectored me further out to the west than I really wanted to be, and I had to stay fairly low. This, combined with the now-steady rain, was starting to give me concern. As I reached Antelope Island, I requested to go direct to Ogden (OGD) since the rain looked at least a bit lighter that way (and it was more on my desired route). I was allowed to turn east as long as I stayed low (about 1,700 AGL at this point).

I puttered along, with the rain not really causing me much trouble, but lowering the visibility through the canopy. I finally made it out the north side of the Class B, and was cleared to proceed on course. I planned to fly a standard VFR altitude of 11,500 feet, but the clouds were lower in this area, so I had to stay a bit lower. I was able to "cheat" a little, by staying around 10,000 feet over terrain that had risen to about 7,000 (so, with less than 3,000 AGL, exempt from the "hemispheric rule"). I asked a few times what the precipitation looked like to the north, and was basically told that "what you see is what it is". So I continued to dodge heavier showers and aim for the higher visibility all the way up to Malad City, Idaho.

There, I could look back and see the rain from the other side. It was still overcast, but the clouds were much higher, there was the rare spot of sunlight peeking through, and I could climb up to 11,500 as planned. This was all the more desirable, since 10,000 had put me under the radar coverage, so I had to call ZLC back and request it again.

The rest of the flight went on without incident, although I did still pick up some early-afternoon thermal turbulence in Montana. I was happy to have successfully navigated and changed course as necessary to thread through the rain. It was also nice to have spent so much time in the air traffic environment. If you haven't yet given it a try, go for it!

Sunday, July 20, 2008

In the "System"

I flew down yesterday and tried to cover some new ground -- so to speak. I made a fuel stop in Idaho Falls and then landed in Salt Lake City, with some hours that were very different than any that I've flown so far.

I've made long cross-country flights before, but this was the first done solo (long being anything than the one required for the certificate). It also included a trip through the Salt Lake Class B airspace to U42.

I got a late start -- due to the fuel truck taking a very long time to get around to the plane -- so I was in the heat a little more than I wanted, but it worked out okay. A little turbulence through Idaho, but nothing worse than what I've had before.

The first leg of the trip was also over fairly familiar country, so I took the time to mentally go over (again) what I would be doing as I got into the Salt Lake area. I knew that it can sometimes be difficult to obtain a clearance into Class B. Sometimes it's due to the volume of air traffic, sometimes just because it's hard to get a word in on the radio in time. My plan was to try to obtain "flight following" so that I was already in the air traffic system as I arrived near Salt Lake City.

I knew the basics, but a search for more information led me here and here. What a great insight to know to request flight following while still on the ground! This was great, and it's exactly what I did in Idaho Falls. After fueling, I got on with ground control and announced my regular "ready to taxi with ATIS information, southbound departure" but this time, "with request". Ground cleared me to taxi and then asked for my request. "Would you be able to process a flight following request to Salt Lake City?"

Sure enough, as I taxiied out, he came back with a Salt Lake Center frequency to call upon leaving the towered airspace. I took off, and contacted ZLC, received transponder code 6060, and was on my way. "Maintain VFR" is basically what each controller in turn told me to do until I actually began to get into the Class B and need specific altitudes and headings. In fact, it was such a slow day that there was only one traffic report as I was about 20 minutes away from my destination. I suppose that made it all the easier to transition all the way in, but it worked just the way it's supposed to.

The one thing that kept me on my toes was that, despite my extensive planning and writing down the various frequencies I thought I would need, all but one were new to me. So, as I would enter a new sector, I would write down the frequencies and have to dial them in before contact. It just goes to show that there will always be something. Another important thing to remember is to not change ANYTHING unless directed by ATC. For instance, as I flew through southern Idaho, the controller lost radar contact and asked for my altitude. That's it. DON'T change frequencies, DON'T change the transponder. About 20 minutes later, I was back on the radar screen as if nothing had happened.

In all, I moved from Salt Lake Center into Salt Lake Approach, and through at least two different air traffic control sectors, then finally released to the CTAF at Salt Lake Municipal #2. I must say, however, that I benefited from it being a fairly slow Saturday, but it was a good chance to fly "in the system".

I've made long cross-country flights before, but this was the first done solo (long being anything than the one required for the certificate). It also included a trip through the Salt Lake Class B airspace to U42.

I got a late start -- due to the fuel truck taking a very long time to get around to the plane -- so I was in the heat a little more than I wanted, but it worked out okay. A little turbulence through Idaho, but nothing worse than what I've had before.

The first leg of the trip was also over fairly familiar country, so I took the time to mentally go over (again) what I would be doing as I got into the Salt Lake area. I knew that it can sometimes be difficult to obtain a clearance into Class B. Sometimes it's due to the volume of air traffic, sometimes just because it's hard to get a word in on the radio in time. My plan was to try to obtain "flight following" so that I was already in the air traffic system as I arrived near Salt Lake City.

I knew the basics, but a search for more information led me here and here. What a great insight to know to request flight following while still on the ground! This was great, and it's exactly what I did in Idaho Falls. After fueling, I got on with ground control and announced my regular "ready to taxi with ATIS information, southbound departure" but this time, "with request". Ground cleared me to taxi and then asked for my request. "Would you be able to process a flight following request to Salt Lake City?"

Sure enough, as I taxiied out, he came back with a Salt Lake Center frequency to call upon leaving the towered airspace. I took off, and contacted ZLC, received transponder code 6060, and was on my way. "Maintain VFR" is basically what each controller in turn told me to do until I actually began to get into the Class B and need specific altitudes and headings. In fact, it was such a slow day that there was only one traffic report as I was about 20 minutes away from my destination. I suppose that made it all the easier to transition all the way in, but it worked just the way it's supposed to.

The one thing that kept me on my toes was that, despite my extensive planning and writing down the various frequencies I thought I would need, all but one were new to me. So, as I would enter a new sector, I would write down the frequencies and have to dial them in before contact. It just goes to show that there will always be something. Another important thing to remember is to not change ANYTHING unless directed by ATC. For instance, as I flew through southern Idaho, the controller lost radar contact and asked for my altitude. That's it. DON'T change frequencies, DON'T change the transponder. About 20 minutes later, I was back on the radar screen as if nothing had happened.

In all, I moved from Salt Lake Center into Salt Lake Approach, and through at least two different air traffic control sectors, then finally released to the CTAF at Salt Lake Municipal #2. I must say, however, that I benefited from it being a fairly slow Saturday, but it was a good chance to fly "in the system".

Thursday, July 17, 2008

Fits and Starts

One month and three days -- that's how long it's been since my last flight. It's been a busy time around here, and we're gearing up to move the family about 80 miles to the east. The last month has seen house hunting and long drives across the countryside for work. And when I'm not doing that, we experience super-cell thunderstorms. And when the weather's clear, surprisingly so is my checking account (I'm looking into some kind of causal relationship).

But now, with an impending strong high pressure system coming into the western U.S., combined with a family trip down to Salt Lake City, it just may be that I'll be able to log another worthwhile cross-country (into some Class B airspace no less). Since it's been so long, I went up for about 45 minutes today in the convective heat and haze just to brush the dust of and -- coincidentally -- work on some crosswind patterns.

It doesn't take long to realize that the memory gets fuzzy fast. Routines break down, checklists are needed just a little more, and small things that were just beginning to become habit now require more conscious thought. Luckily, the big things are still taking care of themselves. I can still do a slip and my ground reference work. I can land in a crosswind. And, I found out a neat little trick in the DA-20 that highlights when you are entering an uncoordinated base-to-final turn. What? That's a very bad thing? You bet it is...

An uncoordinated low-altitude, low-speed turn is bad no matter how you slice it. It is a common error, and one that often has fatal consequences if allowed to get out of hand. Most often, it is the result of trying to "save" a turn that begins to overshoot the final approach course. By using too much left rudder and not enough left aileron, you begin a skid that allows you to lose altitude a little too quickly. Then, if you are not aware of what's happening and allow yourself to pull back on the stick, your airspeed will disappear. That left wing will drop from under you and you'll have about 5 seconds to contemplate your last error.

This clearly did not happen to me.

What did happen, however, is that I entered my turn at just the right altitude where there was a pretty strong wind shear. As the plane dropped through the variable winds, it was buffeted by the many burbles and gusts (also by the thermals coming of the ground). The reaction from the left seat was to try to maintain a steady track around the pattern and a somewhat constant rate of descent. I came through the shear and the plane took a nice yaw to the right, which I counteracted with a left rudder input (keep in mind that I'm bouncing around pretty good, so no control input is lasting more than a few seconds before needing to be opposed).

I also instinctively pulled just a bit on the stick and let the airspeed go from about 70 to 60. Not enough to stall, but enough to make everything turn a little mushy and feel wrong. And what was the "little trick"?

On climbout, I had both vents open due to the heat. As opposed to the trusty Cessna, with vents up above at the wing, the DA-20 has "dashboard" vents on each side. You can aim them in any direction and get a nice blast of ram air. But as the plane bobs and weaves, the jets of air don't come straight out. You can feel them shift around the interior, almost as if you were in an open cockpit feeling the relative wind.

I was having fun experimenting with this new cue, and as I entered the previously mentioned turn, I felt the air do something odd. I can't even tell you what it did, but it wasn't following what I thought it should do. It was enough that, combined with all the other physical happenings, made it clear that I was entering some regime of the flight envelope I didn't want to be in. Of course, all this took place in 30 seconds or less, but it was enough to feel that sinking feeling.

Happily for you and me, all of the burbling and blowing up above didn't hold down where the rubber meets the road. It was a nice, steady 10 knot wind, but with some variable direction between 45 and 90 from the runway. So it was a good dose of WD-40 for my skills and a reminder that while there is a black-and-white answer to stall speed and bank angle, the ragged edge of real weather can turn that to a gray mess very quickly.

But now, with an impending strong high pressure system coming into the western U.S., combined with a family trip down to Salt Lake City, it just may be that I'll be able to log another worthwhile cross-country (into some Class B airspace no less). Since it's been so long, I went up for about 45 minutes today in the convective heat and haze just to brush the dust of and -- coincidentally -- work on some crosswind patterns.

It doesn't take long to realize that the memory gets fuzzy fast. Routines break down, checklists are needed just a little more, and small things that were just beginning to become habit now require more conscious thought. Luckily, the big things are still taking care of themselves. I can still do a slip and my ground reference work. I can land in a crosswind. And, I found out a neat little trick in the DA-20 that highlights when you are entering an uncoordinated base-to-final turn. What? That's a very bad thing? You bet it is...

An uncoordinated low-altitude, low-speed turn is bad no matter how you slice it. It is a common error, and one that often has fatal consequences if allowed to get out of hand. Most often, it is the result of trying to "save" a turn that begins to overshoot the final approach course. By using too much left rudder and not enough left aileron, you begin a skid that allows you to lose altitude a little too quickly. Then, if you are not aware of what's happening and allow yourself to pull back on the stick, your airspeed will disappear. That left wing will drop from under you and you'll have about 5 seconds to contemplate your last error.

This clearly did not happen to me.

What did happen, however, is that I entered my turn at just the right altitude where there was a pretty strong wind shear. As the plane dropped through the variable winds, it was buffeted by the many burbles and gusts (also by the thermals coming of the ground). The reaction from the left seat was to try to maintain a steady track around the pattern and a somewhat constant rate of descent. I came through the shear and the plane took a nice yaw to the right, which I counteracted with a left rudder input (keep in mind that I'm bouncing around pretty good, so no control input is lasting more than a few seconds before needing to be opposed).

I also instinctively pulled just a bit on the stick and let the airspeed go from about 70 to 60. Not enough to stall, but enough to make everything turn a little mushy and feel wrong. And what was the "little trick"?

On climbout, I had both vents open due to the heat. As opposed to the trusty Cessna, with vents up above at the wing, the DA-20 has "dashboard" vents on each side. You can aim them in any direction and get a nice blast of ram air. But as the plane bobs and weaves, the jets of air don't come straight out. You can feel them shift around the interior, almost as if you were in an open cockpit feeling the relative wind.

I was having fun experimenting with this new cue, and as I entered the previously mentioned turn, I felt the air do something odd. I can't even tell you what it did, but it wasn't following what I thought it should do. It was enough that, combined with all the other physical happenings, made it clear that I was entering some regime of the flight envelope I didn't want to be in. Of course, all this took place in 30 seconds or less, but it was enough to feel that sinking feeling.

Happily for you and me, all of the burbling and blowing up above didn't hold down where the rubber meets the road. It was a nice, steady 10 knot wind, but with some variable direction between 45 and 90 from the runway. So it was a good dose of WD-40 for my skills and a reminder that while there is a black-and-white answer to stall speed and bank angle, the ragged edge of real weather can turn that to a gray mess very quickly.

Friday, June 13, 2008

Another First-Timer

My last flight seems more recent than it really was. And I didn't journal it, since much of it can be found here. But it's been nearly two full months since I've flown, mostly due to a persistent winter that just barely released its grip (probably just for a week or so).

So, today's flight was really just a desperate attempt to remain current. The winds have finally died down enough, and the snow, rain, and clouds have moved on into the midwest. The kids are out of school, too. The opportunity was ripe for getting at least one of them into the air for the first time in a small plane.

It worked out that it was my 8-year-old daughter. She was a bit nervous I think, but didn't really let it show. After a boring couple of hours at work to finish up a few things, we went out to the field. There was a reported 12-knot crosswind, but the windsock didn't quite convince me, and the wind had been dying down all afternoon. So I chatted with my instructor for a bit and did a leisurely preflight. The result was enough crosswind to keep me in the game, but not so much to make it uncomfortable.

We were only up for about 45 minutes, but stayed around 1,500 feet above the ground, nice and slow. It was "cool", "awesome", and "fun", and it will be just the first of what I hope are more flights that I will be able to share with my kids. One of these days, I might even be able to convince my wife :-)

Unfortunately, I wasn't thinking when I came in for a landing. I should have taken the opportunity to do two touch-and-go's in addition, to keep my 90-day currency for passengers. Oh well...a good reason to take another flight in the next month. Coincidentally, it will also be about my one-year anniversary of flying. Do I buy flowers for my instructor, or is it vice versa?

So, today's flight was really just a desperate attempt to remain current. The winds have finally died down enough, and the snow, rain, and clouds have moved on into the midwest. The kids are out of school, too. The opportunity was ripe for getting at least one of them into the air for the first time in a small plane.

It worked out that it was my 8-year-old daughter. She was a bit nervous I think, but didn't really let it show. After a boring couple of hours at work to finish up a few things, we went out to the field. There was a reported 12-knot crosswind, but the windsock didn't quite convince me, and the wind had been dying down all afternoon. So I chatted with my instructor for a bit and did a leisurely preflight. The result was enough crosswind to keep me in the game, but not so much to make it uncomfortable.

We were only up for about 45 minutes, but stayed around 1,500 feet above the ground, nice and slow. It was "cool", "awesome", and "fun", and it will be just the first of what I hope are more flights that I will be able to share with my kids. One of these days, I might even be able to convince my wife :-)

Unfortunately, I wasn't thinking when I came in for a landing. I should have taken the opportunity to do two touch-and-go's in addition, to keep my 90-day currency for passengers. Oh well...a good reason to take another flight in the next month. Coincidentally, it will also be about my one-year anniversary of flying. Do I buy flowers for my instructor, or is it vice versa?

Sunday, April 13, 2008

Phoenix

As the Prop Turns

Text and Photos courtesy of Summit Aviation

Yet another reason to be a pilot

Summit Aviation headed to PHX on the 18th of April. Fourteen pilots headed south for 2 days of this spring (which has obviously been more of an ongoing winter). A group of seven aircraft including three Diamond DA-20s, three Diamond DA-40s, and one Cessna left Gallatin field and headed for Driggs, ID for breakfast at the Warbirds Café. After filling up on peanuts and crackers (yeah right) due the Warbirds not being open, we headed for Vernal, UT. The Vernal FBO loaned us some crew transportation and we headed for what appeared to be a barn, but turned out to be the restaurant we had been told about at the airport. After lunch only one of the crew cars decided to run so we began ferrying pilots back to the airport four at a time. We used the community toothbrush at the Vernal FBO and headed for Page, AZ. Lake Powell showed us great sites along the route and made the exhausting autopilot flying seem less mentally taxing. Fuel in Page and back airborne for a corridor to take us over the Grand Canyon, an experience every pilot should be able to put in their logbook. Finally, cleared to land Runway 30L in Williams Gateway, AZ (just outside PHX) and with 10,000ft of runway, we figured landing assured.

85 to 90 degree heat in PHX seemed great the next few days. We golfed and found some great sushi and Mexican food, some of us got to see family and friends in the area.

The return home started with a morning flight to Sedona, AZ for breakfast. Awesome views of southwestern rock formations with bright colors made for a lot of photo opportunities. Another trip over the Grand Canyon and we then departed AZ and went on to Southern Utah. Good weather and a little tailwind to another fuel stop in Provo. Utah passed under us and into Idaho where the weather started to deteriorate. We stopped in Idaho Falls to look at the passes to get into Montana. Raynold’s pass south of Henry’s Lake proved socked in so the group went west to Monida Pass south of Dell, MT and was able to get through with no trouble. Over Dillon and a right turn at the north end of the Tobacco Root mountains and we were home free. We had a great trip, great flying, great food, and great time amongst pilots.

Friday, April 4, 2008

All Over the Glass

It is spring, isn't it? You wouldn't know it around here. Snow last week, and more tomorrow. But in between, it's been fairly nice. The winds pick up every day, so I keep an eye on those, and today seemed to be a good day to try out a new set of wings.

After a few weeks of reading up on the G1000 (the Garmin "Glass Cockpit"), I scheduled some time in the school's DA-40. This is the four-seat, bigger cousin of the DA-20 that I have flown up until now. Not only that, but it has a constant-speed propeller (yet another level of complexity). It is also an extra $50 an hour, but who's counting?

The idea behind the glass cockpit is taking out all of the dials and needles that you may be familiar with (basically any general aviation panel before Y2K) and replacing them with two large, flat-panel displays more like an airliner or fighter jet. All of the same information is there, albeit in vastly different forms. And there are plenty of new features, with literally several new "bells and whistles". Every time you disconnect the autopilot or deviate from a set altitude, the plane will ding, bong, and beep to let you know.

The biggest hurdle, especially after having an instrument scan burned into your brain during primary training, is looking at different parts of the panel and reading scrolling numbers rather than spinning dials. For me, this was a bit difficult, and I kept finding my eyes drawn to the points in space that I would expect to see an altimeter or airspeed indicator. Even some of the switches (especially the flaps) are in a different place, and it's a reach - with eyes inside the cockpit - to find the right spot.

The constant-speed prop is also a new idea for me. It means another lever to fiddle with during changes in the flight profile (climbing, leveling off, and descending). The trick is to know what power and prop settings will get you what you want, putting them there, and letting the plane settle into equilibrium - which takes a few extra seconds compared to the smaller craft.

The lesson today was the first to be checked out to solo this particular plane. We did some steep turns (which came out quite well, thank you), slow flight, and stalls. In all, this is a very smooth plane, and it responds very well to control inputs, both on the ground and in the air. I really enjoyed the flight, but it will take much more practice to be as comfortable with it as the DA-20.

As an added bonus, the light winds that had been the rule for the day decided to give way to a 20-knot surface crosswind that made takeoff interesting and landing impossible. I had an unfamiliar plane with unfamiliar handling, sight pictures, sounds, and feel - and I had left rudder to the floor during the roundout. It wasn't coming together, and I had to go around for a landing on the crosswind runway.

Not bad for the frequency of my flying lately.

After a few weeks of reading up on the G1000 (the Garmin "Glass Cockpit"), I scheduled some time in the school's DA-40. This is the four-seat, bigger cousin of the DA-20 that I have flown up until now. Not only that, but it has a constant-speed propeller (yet another level of complexity). It is also an extra $50 an hour, but who's counting?

The idea behind the glass cockpit is taking out all of the dials and needles that you may be familiar with (basically any general aviation panel before Y2K) and replacing them with two large, flat-panel displays more like an airliner or fighter jet. All of the same information is there, albeit in vastly different forms. And there are plenty of new features, with literally several new "bells and whistles". Every time you disconnect the autopilot or deviate from a set altitude, the plane will ding, bong, and beep to let you know.

The biggest hurdle, especially after having an instrument scan burned into your brain during primary training, is looking at different parts of the panel and reading scrolling numbers rather than spinning dials. For me, this was a bit difficult, and I kept finding my eyes drawn to the points in space that I would expect to see an altimeter or airspeed indicator. Even some of the switches (especially the flaps) are in a different place, and it's a reach - with eyes inside the cockpit - to find the right spot.

The constant-speed prop is also a new idea for me. It means another lever to fiddle with during changes in the flight profile (climbing, leveling off, and descending). The trick is to know what power and prop settings will get you what you want, putting them there, and letting the plane settle into equilibrium - which takes a few extra seconds compared to the smaller craft.

The lesson today was the first to be checked out to solo this particular plane. We did some steep turns (which came out quite well, thank you), slow flight, and stalls. In all, this is a very smooth plane, and it responds very well to control inputs, both on the ground and in the air. I really enjoyed the flight, but it will take much more practice to be as comfortable with it as the DA-20.

As an added bonus, the light winds that had been the rule for the day decided to give way to a 20-knot surface crosswind that made takeoff interesting and landing impossible. I had an unfamiliar plane with unfamiliar handling, sight pictures, sounds, and feel - and I had left rudder to the floor during the roundout. It wasn't coming together, and I had to go around for a landing on the crosswind runway.

Not bad for the frequency of my flying lately.

Saturday, March 22, 2008

First Passengers

The forecast was a bit sketchy, with some clouds and wind anticipated for the afternoon. I kept an obsessive watch on the satellite picture and the nearby METAR's to be sure that my first passenger flights would be good experiences.

The weather really could not have been much better. Aside from a few gusty surface winds at my destination, the three total flights (my father-in-law cross-country one way, my brother-in-law's short hop over the local patch, and my mom's trip back to the home base) turned out better than expected.

It was a beautiful day, with scattered snow showers masking some distant mountain peaks, but clear skies and 15-20 knot winds aloft. I even got to fly the school's brand new (only 190 hours-old) DA-20, just recently released from dual-only flight. Each cross-country was only about 60 miles, and the local trip "around town" was only about 20 minutes, but just perfect for first flights. My mom was the only one that has had general aviation experience, at least in the cockpit (and she's also currently in ground school). My father-in-law went skydiving once, but he apparently was a little too preoccupied to pay much attention to the aircraft aspect of the trip.

All had a great day, and with two more hours of cross-country time, it was worthwhile for me as well. I even impressed myself with some quick rudder action in a gusty crosswind for a glass-smooth touchdown. I was proud to show off my new skills, and it was neat to have someone on hand to take some pictures for once.

Preflight photo op

Looking out over town

You can see my house in this shot

On the way back

The weather really could not have been much better. Aside from a few gusty surface winds at my destination, the three total flights (my father-in-law cross-country one way, my brother-in-law's short hop over the local patch, and my mom's trip back to the home base) turned out better than expected.

It was a beautiful day, with scattered snow showers masking some distant mountain peaks, but clear skies and 15-20 knot winds aloft. I even got to fly the school's brand new (only 190 hours-old) DA-20, just recently released from dual-only flight. Each cross-country was only about 60 miles, and the local trip "around town" was only about 20 minutes, but just perfect for first flights. My mom was the only one that has had general aviation experience, at least in the cockpit (and she's also currently in ground school). My father-in-law went skydiving once, but he apparently was a little too preoccupied to pay much attention to the aircraft aspect of the trip.

All had a great day, and with two more hours of cross-country time, it was worthwhile for me as well. I even impressed myself with some quick rudder action in a gusty crosswind for a glass-smooth touchdown. I was proud to show off my new skills, and it was neat to have someone on hand to take some pictures for once.

Preflight photo op

Looking out over town

You can see my house in this shot

On the way back

Monday, March 10, 2008

Finally - Some Flight Time

About time. After the fiasco last time, I was definitely ready to get back into the air and keep my skills up. Since I eventually want to get an instrument rating, I've been working on planning mostly cross-country flights to work on navigation. It's not really instrument training, but it's work to polish up the flying and tighten the tolerances.

Today's flight was the same one that I had planned for last time. This time, it went off without a hitch...well, maybe just one. The winds were a bit much and I never made up my time flying into a headwind, arriving back home a bit late. But if that's the worst of it, I'm happy.

The trip was just two legs, with a VOR in the middle. I don't let the apparent simplicity of the navigation to make for a "routine" flight though. I monitored my progress, noted times at checkpoints, cross-checked my VOR with my GPS with my chart, and paid close attention to my heading and course. I also went through the radio frequencies of the fields I passed and kept in the habit of checking my engine instruments every few minutes.

Arriving in the vicinity of my destination (an uncontrolled field) I made the radio calls and kept an eye on a departing flight. Overflying the field, I checked the wind and then went out wide, descended to the pattern, and came in for a good landing. After a short stop to reverse the GPS flightplan and double-check my times, it was back into the air for the trip back.

It was a good exercise to arrive at an unfamiliar field, and I tried to maintain my altitude a bit better than I usually do. It still needs work, but it was a good post-checkride "lesson".

Today's flight was the same one that I had planned for last time. This time, it went off without a hitch...well, maybe just one. The winds were a bit much and I never made up my time flying into a headwind, arriving back home a bit late. But if that's the worst of it, I'm happy.

The trip was just two legs, with a VOR in the middle. I don't let the apparent simplicity of the navigation to make for a "routine" flight though. I monitored my progress, noted times at checkpoints, cross-checked my VOR with my GPS with my chart, and paid close attention to my heading and course. I also went through the radio frequencies of the fields I passed and kept in the habit of checking my engine instruments every few minutes.

Arriving in the vicinity of my destination (an uncontrolled field) I made the radio calls and kept an eye on a departing flight. Overflying the field, I checked the wind and then went out wide, descended to the pattern, and came in for a good landing. After a short stop to reverse the GPS flightplan and double-check my times, it was back into the air for the trip back.

It was a good exercise to arrive at an unfamiliar field, and I tried to maintain my altitude a bit better than I usually do. It still needs work, but it was a good post-checkride "lesson".

Thursday, March 6, 2008

Right Rudder?

It's been nearly three weeks since my checkride, and I haven't flown once. Today, the weather was good enough to give it a shot.

I planned to fly a short cross-country to stay current and start building up those hours in anticipation of a future instrument rating. The weather was a bit iffy, with some winds and scattered clouds, but I studied all the information and obtained a briefing, and I felt good to go. Even so, I had an alternate plan in mind should the clouds come in faster than forecast. Turns out, I needed to completely deviate from my plan when the plane decided to act up....on the ground.

I went through my startup and got all my things organized, even putting in my short hop to the GPS flight plan. I taxied down to the end of the runway and pulled off to do my runup. As I turned the plane around, I felt and heard a POP and the right brake pedal went "to the floor".

As an aside, the Diamond DA-20 has no steerable nosewheel. It is freely castering and simply reacts to the turning caused by applying one or the other of the main wheel brakes. This means that with no brake on the right side, I could not technically turn right. Fortunately, this plane also has a sizable rudder and is light enough that even a normal taxi speed provides enough rudder authority to maintain direction.

I immediately knew that my "flight" was over, and as I fiddled with the pedals to confirm that just one side was affected, I was on the radio requesting a taxi back and explaining my situation so as not to be put in any tight spots. The controller was very understanding and asked if I needed him to call over to the flight school to have someone come out to help. I said, "Negative" and he cleared me to taxi back.

There was another plane waiting to taxi to takeoff, and he was informed that I was moving slow, which caused no problems. As I taxied, I carefully experimented to see just how marginal my directional control was. It didn't seem too bad, but I knew I would have to slow down as I got up to the ramp area and would exit the taxiway toward lots of (expensive) parked aircraft. The waiting plane was cleared to taxi after I would clear the taxiway, and I was cleared (again) to continue on my way. I "rogered" and started to turn off the taxiway.

As I slowed down, it didn't take long for my lack of right-turning ability to catch up with me. At still a fairly normal taxi speed for the area, I had to decide what was going to happen next. The throttle already at idle, it was either speed up a bit and get the rudder into the mix again, or pull the mixture, cut the engine, and use just left brake to come to a stop. It quickly became apparent that more speed was definitely not a good thing at this point. I also noticed out of the corner of my eye that a couple of folks from the flight school were walking out toward me, apparently aware of my predicament.

The slow speed resulted in a nearly 90-degree turn to the left as the engine and wheels stopped turning at about the same time. I paused and told the ground controller that "We'll have to push it off." I was stopped just inside the dividing line between the ramp (a "non-movement" area) and the taxiway (a "movement" area). Movement areas require controller clearance to enter or operate within (whether you are a plane, vehicle, or pedestrian). Since I still technically had a clearance to "taxi" back to the hangar, it felt reasonable that we would simply do so. I finished completely shutting down the systems, including the radio, and hopped out as one of the school staff, a student from the school, and a lineman from next-door got to the plane.

We began pulling/pushing the plane up the ramp, and as we did so, we were intercepted by one of the airport authorities who was very upset that we had created a "pedestrian incursion" in a movement area without controller clearance. As it turned out, according to the CFI that came out, the controller had called the school anyway, unbeknownst to me, and despite my original answer, and they had come out at his request. Since I was still a few hundred feet from the hangar, it felt good to see some help coming over.

Anyway, I have a feeling this little incident might not be over, but I don't see much that I could have done differently, other than just sit there and wait for help. I felt that the controller knew what was going on and that once I shut the plane down, I would not have a radio, but there might be some special procedure for a case like this that I'm unaware of. If so, I will bet that I will find out all about it in the near future, in very great detail.

I planned to fly a short cross-country to stay current and start building up those hours in anticipation of a future instrument rating. The weather was a bit iffy, with some winds and scattered clouds, but I studied all the information and obtained a briefing, and I felt good to go. Even so, I had an alternate plan in mind should the clouds come in faster than forecast. Turns out, I needed to completely deviate from my plan when the plane decided to act up....on the ground.

I went through my startup and got all my things organized, even putting in my short hop to the GPS flight plan. I taxied down to the end of the runway and pulled off to do my runup. As I turned the plane around, I felt and heard a POP and the right brake pedal went "to the floor".

As an aside, the Diamond DA-20 has no steerable nosewheel. It is freely castering and simply reacts to the turning caused by applying one or the other of the main wheel brakes. This means that with no brake on the right side, I could not technically turn right. Fortunately, this plane also has a sizable rudder and is light enough that even a normal taxi speed provides enough rudder authority to maintain direction.

I immediately knew that my "flight" was over, and as I fiddled with the pedals to confirm that just one side was affected, I was on the radio requesting a taxi back and explaining my situation so as not to be put in any tight spots. The controller was very understanding and asked if I needed him to call over to the flight school to have someone come out to help. I said, "Negative" and he cleared me to taxi back.

There was another plane waiting to taxi to takeoff, and he was informed that I was moving slow, which caused no problems. As I taxied, I carefully experimented to see just how marginal my directional control was. It didn't seem too bad, but I knew I would have to slow down as I got up to the ramp area and would exit the taxiway toward lots of (expensive) parked aircraft. The waiting plane was cleared to taxi after I would clear the taxiway, and I was cleared (again) to continue on my way. I "rogered" and started to turn off the taxiway.

As I slowed down, it didn't take long for my lack of right-turning ability to catch up with me. At still a fairly normal taxi speed for the area, I had to decide what was going to happen next. The throttle already at idle, it was either speed up a bit and get the rudder into the mix again, or pull the mixture, cut the engine, and use just left brake to come to a stop. It quickly became apparent that more speed was definitely not a good thing at this point. I also noticed out of the corner of my eye that a couple of folks from the flight school were walking out toward me, apparently aware of my predicament.

The slow speed resulted in a nearly 90-degree turn to the left as the engine and wheels stopped turning at about the same time. I paused and told the ground controller that "We'll have to push it off." I was stopped just inside the dividing line between the ramp (a "non-movement" area) and the taxiway (a "movement" area). Movement areas require controller clearance to enter or operate within (whether you are a plane, vehicle, or pedestrian). Since I still technically had a clearance to "taxi" back to the hangar, it felt reasonable that we would simply do so. I finished completely shutting down the systems, including the radio, and hopped out as one of the school staff, a student from the school, and a lineman from next-door got to the plane.

We began pulling/pushing the plane up the ramp, and as we did so, we were intercepted by one of the airport authorities who was very upset that we had created a "pedestrian incursion" in a movement area without controller clearance. As it turned out, according to the CFI that came out, the controller had called the school anyway, unbeknownst to me, and despite my original answer, and they had come out at his request. Since I was still a few hundred feet from the hangar, it felt good to see some help coming over.

Anyway, I have a feeling this little incident might not be over, but I don't see much that I could have done differently, other than just sit there and wait for help. I felt that the controller knew what was going on and that once I shut the plane down, I would not have a radio, but there might be some special procedure for a case like this that I'm unaware of. If so, I will bet that I will find out all about it in the near future, in very great detail.

Saturday, February 16, 2008

The Big Day, Part 2

The details of the maneuvers clearly aren't all that interesting. If you know the practical test standards, you already know what to expect and if you know that I passed (I did), then you know what I had to do. The sequence went something like this:

Climb on course on the first leg of our fictional cross-country

Look for landmarks and compare them with the chart

Navigate based on the VOR and based on GPS

Level off at desired altitude

Oops, you flew into a cloud. Put on the hood and get us out of here.

Pretend to call the tower and follow their directions to get us back to the field

You are in an unusual attitude, get us out

Okay, hood off, get us to the practice area for slow flight

"I want that stall horn screaming nice and loud."

Some slow turns, then a power-on stall, a power-off stall, a turning stall, and then another turning stall

Show me some steep turns (Yay!)

Oops, your engine failed, get us down

Okay, your engine's back; stay low and do a turn around a point

"What do these buttons do?" (While I'm focused on the turn in a 20-knot wind)

Let's head back in for some touch-and-go's

Show me a normal landing, followed by a soft-field takeoff

Show me a soft-field landing with a slip

Do short-field landing, with a stop on the runway, followed by a short-field takeoff

Land on that spot right there

No, that other spot....

Okay, let's go in. Good job.

That may seem like a short list, and it felt like it was only as long as you probably took to read it. When it was all done, there were a few tips that he had (not surprising for a 50-hour student), but nothing that was a deal-killer. So, I'm now qualified to lead others into the great beyond...no, wait, that's not what I meant. I mean I'm now certified to demonstrate hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror. Yeah, that's more like it.

See you up there.

Climb on course on the first leg of our fictional cross-country

Look for landmarks and compare them with the chart

Navigate based on the VOR and based on GPS

Level off at desired altitude

Oops, you flew into a cloud. Put on the hood and get us out of here.

Pretend to call the tower and follow their directions to get us back to the field

You are in an unusual attitude, get us out

Okay, hood off, get us to the practice area for slow flight

"I want that stall horn screaming nice and loud."

Some slow turns, then a power-on stall, a power-off stall, a turning stall, and then another turning stall

Show me some steep turns (Yay!)

Oops, your engine failed, get us down

Okay, your engine's back; stay low and do a turn around a point

"What do these buttons do?" (While I'm focused on the turn in a 20-knot wind)

Let's head back in for some touch-and-go's

Show me a normal landing, followed by a soft-field takeoff

Show me a soft-field landing with a slip

Do short-field landing, with a stop on the runway, followed by a short-field takeoff

Land on that spot right there

No, that other spot....

Okay, let's go in. Good job.

That may seem like a short list, and it felt like it was only as long as you probably took to read it. When it was all done, there were a few tips that he had (not surprising for a 50-hour student), but nothing that was a deal-killer. So, I'm now qualified to lead others into the great beyond...no, wait, that's not what I meant. I mean I'm now certified to demonstrate hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror. Yeah, that's more like it.

See you up there.

The Big Day, Part 1

I arrived a bit early, so I sat in the car and called up WX-BRIEF to get a full weather briefing. Since we weren't actually going to make the flight, it was mostly academic, but you have to do it to be able to explain why we would or would not make the flight.

When the time came, I hopped over to the flight school, where the examiner was just finishing with the prior student. I took a few minutes to plug in the weight and balance calculations (after realizing that I didn't have the actual airplane weight on hand last night). But I didn't even have time to put in the wind corrections to my navigation log; it was time to get started.

The oral portion of the exam covered a wide range of information, but we spent (what seemed to me) to be a lot of time on chart interpretation, airspace, and cross-country scenarios. Luckily, this is an area that I am very comfortable with. We ran through general questions about carrying passengers, what it took to be legal from private pilot, airplane, weather, and physiological perspectives, and talked about various obscure regulations and their interpretations.

I didn't have 100% of the answers, but that's expected. I at least knew when I was on the ragged edge of my knowledge, but we only looked up one thing in the regulations. Most of the time, it was a small detail, and the examiner could tell that I had the general ideas.

Before I knew it, it was time to fly.

We went down to preflight, and the examiner said, "Pretend I'm a regular passenger wondering what it is you're doing. Explain it to me." So that's what I did. Every single item, as if I was giving a ride to a friend who knew nothing about airplanes. I felt like I was performing for someone who had seen this show hundreds of times and knew exactly how it would end. I even felt like I was talking too much. In fact, my effort to do so made me overlook an area of the checklist, but since it's all habit now, it didn't take long to catch it.

Then we got in the plane and I explained what we would do, the steps I would go through, cockpit radio traffic, emergency procedures, seat belts...the works. During the debrief, the examiner pointed out one thing I didn't mention: the ELT. Well, shoot...there's always something.

We started up and got going, with more questions about airport signs, lights, procedures, and other field-related topics. We got to the runup, and I again explained what we were going to do and why. Then, my heart sank.

The runup involves throttling up to 1700 RPM and checking the magnetos, engine instruments, and flight instruments (especially the vacuum powered ones). As I pushed the throttle in, the RPM was nowhere near steady. There are always some very minor fluctuations - maybe 10 or 20 RPM, but this was +/- 75 RPM without doing anything. It wasn't even clear that we were getting a good magneto check. I sat there flipping the key back and forth, cycling the fuel pump, and generally staring at the tachometer - willing it to just stop waving back and forth. What are we going to do? Cancel the flight? Get another plane? Ack.

The examiner obviously knew I was having a mental breakdown at this point, and figured it might be fouled plugs. He brought the mixture out, which didn't seem to fix it. Then we ran it all the way up to 2000 RPM, but that didn't seem to have any effect either. These planes run at full rich in some very high, hot conditions, so I would have been surprised if it really was too rich on this cold day. We sat there for another minute with the engine up to 1700, back to idle, up to 2000, back to idle. All the other gauges were in the green, and there weren't any funny noises, so, we jointly decided to press on and watch what happened on the runway.

Needless to say, there wasn't a fiery crash....

When the time came, I hopped over to the flight school, where the examiner was just finishing with the prior student. I took a few minutes to plug in the weight and balance calculations (after realizing that I didn't have the actual airplane weight on hand last night). But I didn't even have time to put in the wind corrections to my navigation log; it was time to get started.

The oral portion of the exam covered a wide range of information, but we spent (what seemed to me) to be a lot of time on chart interpretation, airspace, and cross-country scenarios. Luckily, this is an area that I am very comfortable with. We ran through general questions about carrying passengers, what it took to be legal from private pilot, airplane, weather, and physiological perspectives, and talked about various obscure regulations and their interpretations.

I didn't have 100% of the answers, but that's expected. I at least knew when I was on the ragged edge of my knowledge, but we only looked up one thing in the regulations. Most of the time, it was a small detail, and the examiner could tell that I had the general ideas.

Before I knew it, it was time to fly.

We went down to preflight, and the examiner said, "Pretend I'm a regular passenger wondering what it is you're doing. Explain it to me." So that's what I did. Every single item, as if I was giving a ride to a friend who knew nothing about airplanes. I felt like I was performing for someone who had seen this show hundreds of times and knew exactly how it would end. I even felt like I was talking too much. In fact, my effort to do so made me overlook an area of the checklist, but since it's all habit now, it didn't take long to catch it.

Then we got in the plane and I explained what we would do, the steps I would go through, cockpit radio traffic, emergency procedures, seat belts...the works. During the debrief, the examiner pointed out one thing I didn't mention: the ELT. Well, shoot...there's always something.

We started up and got going, with more questions about airport signs, lights, procedures, and other field-related topics. We got to the runup, and I again explained what we were going to do and why. Then, my heart sank.

The runup involves throttling up to 1700 RPM and checking the magnetos, engine instruments, and flight instruments (especially the vacuum powered ones). As I pushed the throttle in, the RPM was nowhere near steady. There are always some very minor fluctuations - maybe 10 or 20 RPM, but this was +/- 75 RPM without doing anything. It wasn't even clear that we were getting a good magneto check. I sat there flipping the key back and forth, cycling the fuel pump, and generally staring at the tachometer - willing it to just stop waving back and forth. What are we going to do? Cancel the flight? Get another plane? Ack.

The examiner obviously knew I was having a mental breakdown at this point, and figured it might be fouled plugs. He brought the mixture out, which didn't seem to fix it. Then we ran it all the way up to 2000 RPM, but that didn't seem to have any effect either. These planes run at full rich in some very high, hot conditions, so I would have been surprised if it really was too rich on this cold day. We sat there for another minute with the engine up to 1700, back to idle, up to 2000, back to idle. All the other gauges were in the green, and there weren't any funny noises, so, we jointly decided to press on and watch what happened on the runway.

Needless to say, there wasn't a fiery crash....

The Big Day (Before)

With everything in order, the checkride was confirmed, the plane was scheduled, and the examiner was given all my information.

I received my "homework" assignment last night at about 7 pm. I had to plan a cross-country flight about 250 miles, over some mountainous terrain. The examiner emailed me a couple of other helpful documents, along with the pertinent weight information for my calculations.

I was up until about 11 staring at the chart and deciding the best course (and, of course, planning how I would justify my decisions), doing all the planning, and writing up the flight plan and navigation log. I used AOPA's flight planner to get the general path and rough time calculations to see if I would need a fuel stop. It didn't look like I would, so I went ahead and made some manual adjustments to the course for terrain and weather considerations. Basically, I didn't want to be over desolate mountains in windy and potentially cloudy conditions.

With no more mental capacity to even crack a book open, I called it a night. I had to be at the airport by noon, so I spent this morning checking the weather and printing out airport diagrams for the departure, destination, and one alternate field.

Then it was off to meet my first "passenger".

I received my "homework" assignment last night at about 7 pm. I had to plan a cross-country flight about 250 miles, over some mountainous terrain. The examiner emailed me a couple of other helpful documents, along with the pertinent weight information for my calculations.

I was up until about 11 staring at the chart and deciding the best course (and, of course, planning how I would justify my decisions), doing all the planning, and writing up the flight plan and navigation log. I used AOPA's flight planner to get the general path and rough time calculations to see if I would need a fuel stop. It didn't look like I would, so I went ahead and made some manual adjustments to the course for terrain and weather considerations. Basically, I didn't want to be over desolate mountains in windy and potentially cloudy conditions.

With no more mental capacity to even crack a book open, I called it a night. I had to be at the airport by noon, so I spent this morning checking the weather and printing out airport diagrams for the departure, destination, and one alternate field.

Then it was off to meet my first "passenger".

Icing on the Cake

I flew again yesterday, but that's just part of the story. Let me invite you into the way-back machine...

Earlier in the week, we had tentatively scheduled my checkride for the 21st of the month. So, I had it all figured out: I would cram for a week, maybe take another flight, and generally polish up the rough edges. Forward to yesterday, which, on a totally unrelated note ended up being a "stay-home" day for me. Working away on the computer, I noticed a call from my flight instructor. A checkride cancellation came up, and did I want to do it on Saturday...Heck, yeah...wait, you mean tomorrow?!

With much drama, fanfare, bribery, and corruption, we managed to work out babysitting and other assorted scheduling nightmares, and I called the instructor back to confirm that it would work. "Okay, can you come down right now and we'll do some review and pattern work?" "Uh, yeah, I guess I can do that, too." So much for working from home. Now, I had literally about 24 hours to make one last flight and cram as much as I could before today's examination. Whew.

I won't bore you with yesterday's work, since there really wasn't much to it. We did about 45 minutes' worth of touch-and-go's, and then went over the application form. We spent more time on paperwork than anything else.

But then came the really fun part....

Earlier in the week, we had tentatively scheduled my checkride for the 21st of the month. So, I had it all figured out: I would cram for a week, maybe take another flight, and generally polish up the rough edges. Forward to yesterday, which, on a totally unrelated note ended up being a "stay-home" day for me. Working away on the computer, I noticed a call from my flight instructor. A checkride cancellation came up, and did I want to do it on Saturday...Heck, yeah...wait, you mean tomorrow?!

With much drama, fanfare, bribery, and corruption, we managed to work out babysitting and other assorted scheduling nightmares, and I called the instructor back to confirm that it would work. "Okay, can you come down right now and we'll do some review and pattern work?" "Uh, yeah, I guess I can do that, too." So much for working from home. Now, I had literally about 24 hours to make one last flight and cram as much as I could before today's examination. Whew.

I won't bore you with yesterday's work, since there really wasn't much to it. We did about 45 minutes' worth of touch-and-go's, and then went over the application form. We spent more time on paperwork than anything else.

But then came the really fun part....

Thursday, February 14, 2008

Tying Up Loose Ends

After taking the prior dual flight's recommendations, last time was a good practice, and it paid off today. As expected, task #1 was more steep turns. The first one was a bit wobbly, and I told the instructor that I probably just needed to warm up first. The next ones and a couple more turned out nearly perfect. He was satisfied, and said that I had come a long way since a few lessons ago.

After taking the prior dual flight's recommendations, last time was a good practice, and it paid off today. As expected, task #1 was more steep turns. The first one was a bit wobbly, and I told the instructor that I probably just needed to warm up first. The next ones and a couple more turned out nearly perfect. He was satisfied, and said that I had come a long way since a few lessons ago.We did some slow flight and yet more hood work (I'm up to 5.5 hours), which all went smoothly with no difficulties. Then we did some turning stalls, which I haven't done in a long time. These were a bit more of a challenge than I remember, and it was tricky to give just the right amount of rudder to stay coordinated. But we didn't get into a spin, so it was acceptable.

Then we came back into the pattern and did some touch-and-go's. I made extra effort to stay right on the centerline, and T.I. was impressed. I said I did 7 landings last time and paid special attention to it, so it paid off.

Everything went well, and we have tentatively scheduled the checkride for next week, but it still might not happen if work and weather don't cooperate; we'll have to see.

Tuesday, February 12, 2008

The Steep Turn Solution

Today, after a big hiatus due to lousy weather and an even lousier flu, I flew solo to whip these steep turns. It's been a long time since I flew, and I have been waiting to put to practice all of the mental turns I've had looping through my head for weeks.

I decided to just focus on the basics, and just kept going back and forth, with a few little coordination exercises just for good measure. I wanted to just go back to "first principles" and work through the turns step by step. The most significant adjustment was that I didn't use the trim at all this time. Most often, my instructor has me trim as I establish the bank, and then as I roll out, I need to trim back to straight and level. I made the choice to just muscle through the turns, which ended up working out much better today.

It may just be a matter of sheer practice, but I felt that the control pressures gave me better feedback about what the plane was about to do. In any event, while not every turn was a winner, I was significantly better than before, and more consistent. The other adjustment was to pick a spot on the windshield for a horizon reference, something that we've done before, but not emphasized. This time, I was narrowly focused on the horizon as I entered the turn, and things started out a lot more stable.

It meant that I gave up a few seconds of outside scanning, but in a steep turn, the world spins by pretty fast anyway. The end result was that I was more stable in the turn entry, and I could better anticipate the altitude fluctuations and arrest them before they busted minimums. After going around on the carousel for an hour or so, I decided to work on my landings.

I entered the pattern, and did a bunch of approaches, making extra sure to stay on the right side of the power curve. As is my habit, I still hold a bit too much speed sometimes (especially solo, when the throttle has to be way out for a normal descent), and I made sure to bleed off energy before final. On my first approach, I had to correct for a slight crosswind down to about 100 feet AGL, and I had to make a conscious effort to keep lined up. It's been a long time since I had a real crosswind touchdown, so even a bit of practice at altitude is good.